In Translation: Japan

I’m on a bit of a personal mission to read more books in translation this year. You could call it guilt over my monolingualism, but I do also think it’s important to read literature from other places in the world. I’m starting with Japan because I recently read and enjoyed Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata and Territory of Light by Yūko Tsushima. Japanese literature also seems to be having a bit of a moment right now. The entire month of January was dubbed “Japanuary” at Foyles bookstore in London this year, and it seems like every week there’s a new translation or edition of a Japanese book published by major American and British presses. Also there are a lot of popular novels by Japanese authors about cats, and I love cats.

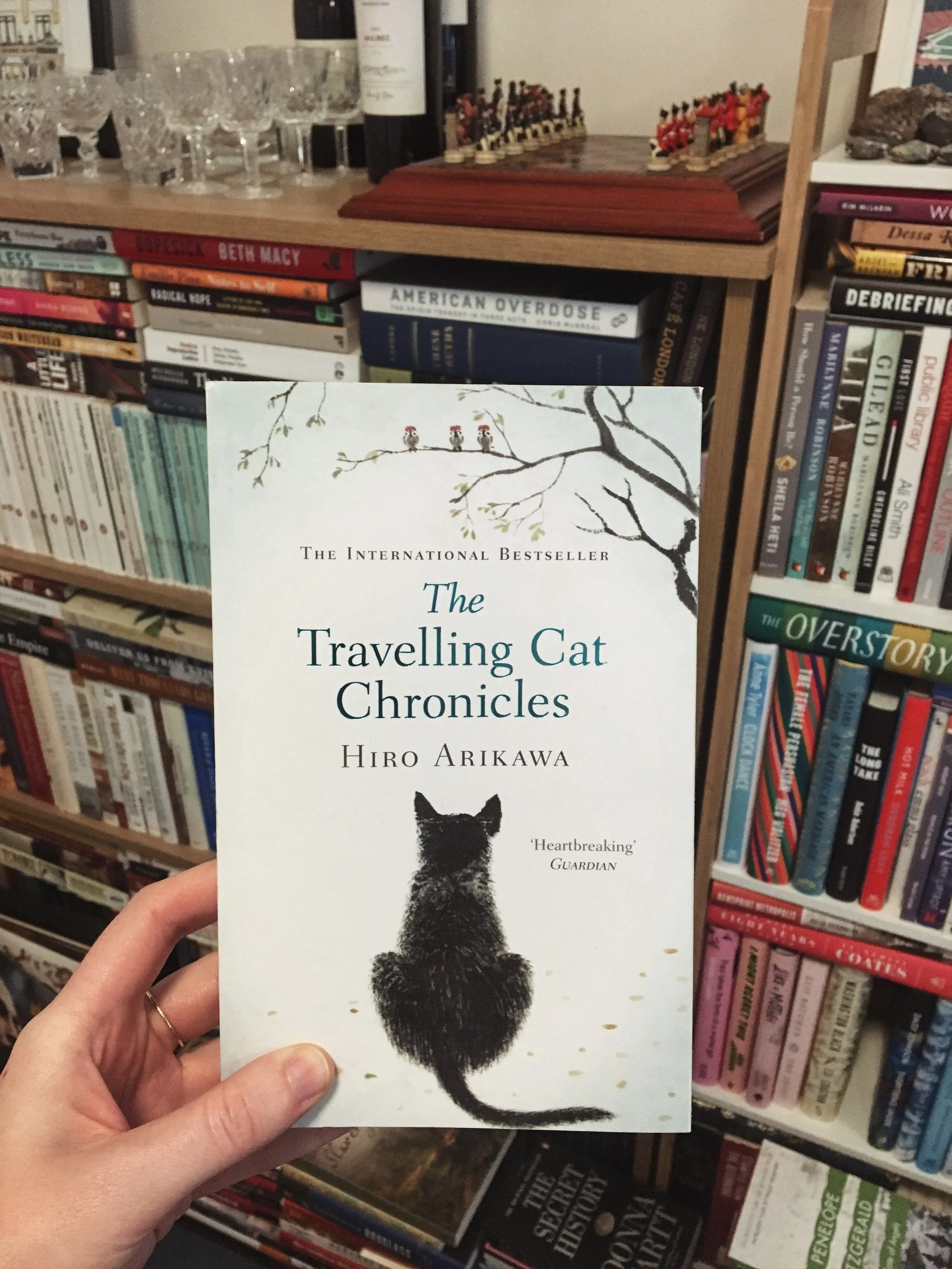

The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa

Half of this book is written from the perspective of a cat, and I loved it. Nana and his owner Satoru travel around Japan in a silver van visiting people from Satoru’s past. In the process, we learn about his life story and how his relationship with Nana came to be. Arikawa has created a unique and utterly charming narrative voice for Nana the cat, and this book is a beautiful story about love and friendship and the bonds between people and their pets.

If you aren’t a pet person and read that sentence thinking this book isn’t for you, I can reassure you it’s not heavy-handed, and that the book has a plot line and character development beyond just having a cat in the story. Arikawa’s writing is spare and clear but still manages to be full of emotion, and she plays with time, setting and perspective fluidly. The Travelling Cat Chronicles is a lovely and highly readable novel that I recommend wholeheartedly.

Lion Cross Point by Masatsugo Ono

I bought Lion Cross Point in a charity bookstore in Cambridge mostly because I loved the cover of the book. In this case I’m pleased I judged the book by its cover, because this short novel is moving and beautifully written. Ono addresses grief, memory, and childhood trauma through the story of a young boy and his family. Ten-year-old Takeru is a child who has had to grow up too quickly, and Ono deftly captures the straining of a young child trying to be mature beyond his years.

It took me about thirty pages to get a feel for the story and the writing in this book, but once I was hooked I flew threw it. Some sections did read quicker than others, and I definitely preferred the “flashback” scenes - I think because they provided so much of the backstory about Takeru and his family that I initially felt confused about at the start of the book. That’s a reader preference, though I do understand why Ono let the story unfold as it did, and I think the structure of the book, as well as the content, effectively mirrors the ways children remember trauma.

Child of Fortune by Yūko Tsushima

I loved one of Tsushima’s other books Territory of Light, and Child of Fortune did not disappoint. Like Territory of Light, this book revolves around a fraught mother-daughter relationship and what it means to be a single mother in 1970s Japan. In Child of Fortune, Kōko finds herself unexpectedly pregnant at the exact moment her relationship with her 11-year-old daughter Kayako begins to dissolve. Kaya has moved out of her mother’s house and into her aunt’s, and Kōko seems both indifferent to and distraught by this life change. That it’s coupled with an unplanned pregnancy increases Kōko’s feelings of ambivalence and uncertainty, as she struggles to figure out what it is she “should” do, and what it is she actually wants to do.

Tsushima’s writing is beautiful, and in both books of hers that I’ve read she crafts intricate characters and stories within relatively short novels. Child of Fortune is around 150 pages, but nothing is spared in that short length. Tsushima weaves the contemporary plot line with Kōko’s life-history, chronicling her relationships with three romantic partners, as well as her daughter, sister, brother, and parents. Each of these characters has a shape and personality of their own.

The Last Children of Tokyo by Yoko Tawada

I haven’t read much in the category of anthopocene fiction, but this book makes a strong case for the genre. Tawada imagines a future Japan in the wake of human driven climate catastrophe, and the picture is bleak. The elderly never die, but the young are plagued with health problems and struggle to survive. Tawada does a brilliant job of constructing a world that feels at once familiar and strange, and she mirrors that feeling in her characters.

The elderly still feel a sense of confusion about the world they now find themselves in - a constant feeling of “where am I and how did I end up here?” The young, however, know nothing different, and as a result catastrophe feels somehow less than catastrophic. The book touches on what it’s like to navigate through the world in times of profound change. Tawada also captures the kind of ambivalence and apathy with which people approach climate catastrophe. Even as the book’s characters experience pain and suffering as a result of anthropogenic climate change, many of them see these things as quotidian parts of a new everyday life. Sentences like this one capture the dark humor that characterizes many references to climate change I’ve seen in recent fiction (see also Olivia Laing’s Crudo): “Hundreds of thousands of dead washing machines had sunk to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean to become capsule hotels for fish.”

Strange Weather in Tokyo by Hiromi Kawakami

If you’ve read and liked Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman you’ll love Strange Weather in Tokyo. An off-beat love story, Kawakami’s novel follows Tsukiko’s friendship with her former high school teacher. The two haven’t seen each other in nearly twenty years, but they strike up a conversation when they find themselves sitting next to each other in a bar. For months they drink and eat together in local bars, never arranging to meet but always hoping to run into one another. Like Murata’s, Kawakami’s character’s are slightly odd, and Tsukiko in particular feels frustrated with herself about the ways in which she’s not “normal.” Where the characters in Convenience Store Women are intentionally off-putting, however, Tsukiko and Sensei in Strange Weather in Tokyo are deeply relatable and very likable. Without spoiling the ending, I did shed some tears, and that’s something that rarely happens for me in a book.